One of the most valuable primary sources from Chekhov’s Melikhovo years (1892-1898) is the diary kept by his father, Pavel Egorovich Chekhov. His children found his laconic, seemingly random entries to be unintentionally hilarious. Here’s a sample: September 7, 1894: “Rain the whole day. They didn’t give Roman the wallpaper at the station. The stove-builders finished the stove in the living room. The horses were in the garden at night.” But actually Pavel Chekhov’s precise listings of who came and went at Melikhovo make it possible to accurately date the sometimes inaccurate accounts in the memoirs of those who visited Chekhov.

Here is Pavel’s diary entry for the momentous day when Tatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik brought Levitan to Melikhovo to be reunited with Chekhov after more than two years of not speaking to each other: January 2, 1895: “It’s snowing, 8 degrees. They brought a stove with pipes for the kitchen. Antosha went to have lunch with the Priest. T.L. Shchepkina-Kupernik and I.I. Levitan arrived after we had already gone to bed.” Shchepkina-Kupernik described the meeting in her memoirs: As they approached the house Chekhov “came out, looking like he had been drinking. He peered into the darkness to see who was with me–there was a brief pause, and suddenly they both flung themselves towards each other, very, very strongly clasped each other’s hand–and…started talking about the most everyday things: about the road, the weather, Moscow, as if nothing had happened. At dinner, when I saw how Levitan’s beautiful eyes were wet and glistening and how Chekhov’s normally pensive eyes were radiating happiness, I was terribly pleased with myself.”

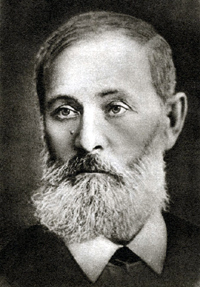

The irrepressible Tatiana Shchepkina-Kupernik was instrumental in both initiating and ending the quarrel between Chekhov and Levitan.

Shchepkina-Kupernik had visited Melikhovo for the first time the previous month. Since Pavel Chekhov was away, the mischievous Shchepkina-Kupernik, obviously with Chekhov’s encouragement, took to adding entries to the diary in his absence, imitating his father’s style: December 4: “Weather is clear. Marinade turned out to be outstanding….” December 5: “Ate wonderful pancakes.”